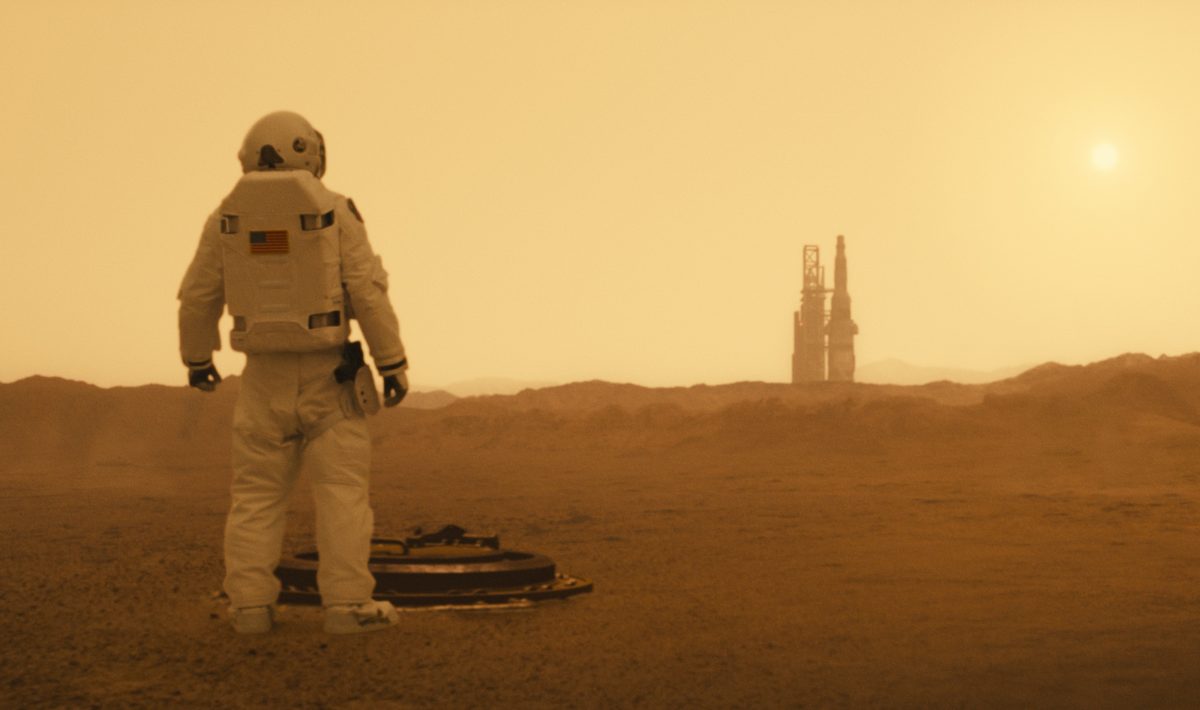

When I watch Hollywood productions, I often remember Slavoj Žižek’s thought about the ability of mass cinema to predict the future[1]. The popular science-fiction cinema smuggles between the lines a warning about the near or distant future, the human condition and the direction in which Western civilization will go. Precisely, James Gray’s Ad Astra is that kind of movie. What is more interesting is not what is happening in the foreground – the son’s difficult relationship with his father, which sometimes seems to be dangerously close to the maudlin style of soap operas – but what can be read in the background.

So I will not focus on simple narrative assumptions: one of the most skillful astronauts of his generation, Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is sent on a mission to contact and later find his father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), space flight hero and pioneer of the new frontier. At stake is not only the mental peace of a man whose father set off on a journey and disappeared when the former was 16 years old, but also the survival of human civilization (it may be that the mysterious Project Lima, of which McBride senior was the commander, is somehow connected to the problem).

Ad Astra presents the “near future” of human civilization, when the colonization of nearby planets will become a way to acquire valuable resources and expansion of space appropriated by man, the expansion of capitalism. One of the questions one can ask is, of course, how people have dealt with the climate crisis. There is not a word about the climate in the film, but you can guess that in the vision of the world presented by Gray problems were somehow mitigated by space travel and thanks to this the neoliberal status quo has been preserved in the world. Ad Astra presents the world in which capitalism has prevailed. And this is a rather dreary victory.

The largest extraterrestrial colony on the moon looks like a gray, lunar Disneyland. The space of the Earth’s satellite has been absorbed by corporations – Subway, DHL[2], etc. – and cheap-showy, tacky visual identification (aliens, stuffed animals, masks, etc.). This is an extremely accurate diagnosis of human civilization – capitalism is everywhere, you can’t escape it. In space, it is easier to find a plastic container with the logo of a known brand than the another human being (or an alien).

You have to pay for everything. During a several-hour trip to the moon, Roy buys a pillow and a blanket to cover his legs – for a horrendous amount of money. As a bonus, passengers get a miniature hand towel. A simple graffiti on the wall of the control room for those visiting Mars draws our attention. It is these elements that make up civilization: dirt, dimly lit, claustrophobic rooms, discomfort advertised as a civilization miracle. Every scene of this type combined probably last less than a minute, but it is these subtle comments on Western civilization that make James Gray’s film interesting.

Another, only slightly marked thread, is the struggle for resources, commented by the hero literally in one sentence. While traveling from a civilian colony to a military base on the moon, a convoy carrying Roy is attacked by pirates hunting for valuable resources. It is enough to go outside the space appropriated by neon lights, logos and brands, to come across a wild fight with capitalist moloch. Although in the film we do not see how the class tensions are unfolding in this “nearby” world, one can guess that this piracy did not come from nowhere.

And how, actually, is a person treated in a reality strictly controlled by the government agency SPACECOM? Everyone who wants to travel in space (you can guess that not only in space) must regularly undergo psychological tests, on the basis of which the appropriate decision is issued. There is no place for emotions which need to be suppressed. Brad Pitt’s acting bears a striking resemblance of Ryan Gosling from Drive (2011) or Only God Forgives (2013) by Nicolas Refn. A face almost devoid of mimicry, which does not even show a curvature during adrenaline rushes (we can count on a slight nervous tick at most), perfectly suits the world in which capitalism has irreversibly won. Associations with Orwell (on level of control, anxiety and hopelessness) will be appropriate.

The design of space rockets, colonial base interiors and orbital stations should be praised. Rockets, as in reality, are calculated for efficiency and for saving valuable space. Interiors and machines look as if they were assembled hastily by some sort of MacGyver: from scrap metal and available items. In the film, we will not find spaces dedicated to entertainment, extensive bars (as in Morten Tyldum’s Passengers from 2016), a gym or a kitchen with funny, space food. Here, liquid food is taken through the tube, directly into the stomach. These are space travels faithfully tailored to the current technological possibilities.

So, Žižek’s recognition of Hollywood science-fiction

as a warning for the future proves to be correct. Like the heroes facing

loneliness in space, balancing on the verge of madness, we can sometimes bend

over the thought that perhaps saving civilization in this form is a risk not

worth the reward and instead of heading to the stars, we should look at the Earth

that we have under our feet.

[1] I can refer here to The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (dir. Sophie Fiennes, 2006), a visual lecture by Žižek on the borderline of philosophy and history of cinema, as well as to Slovenian pop-philosopher’s comments about Elysium (dir. Neill Blomkamp, 2013).

[2] This, of course, is also somewhat funny – the product placement in the film was set in a definitely negative way.