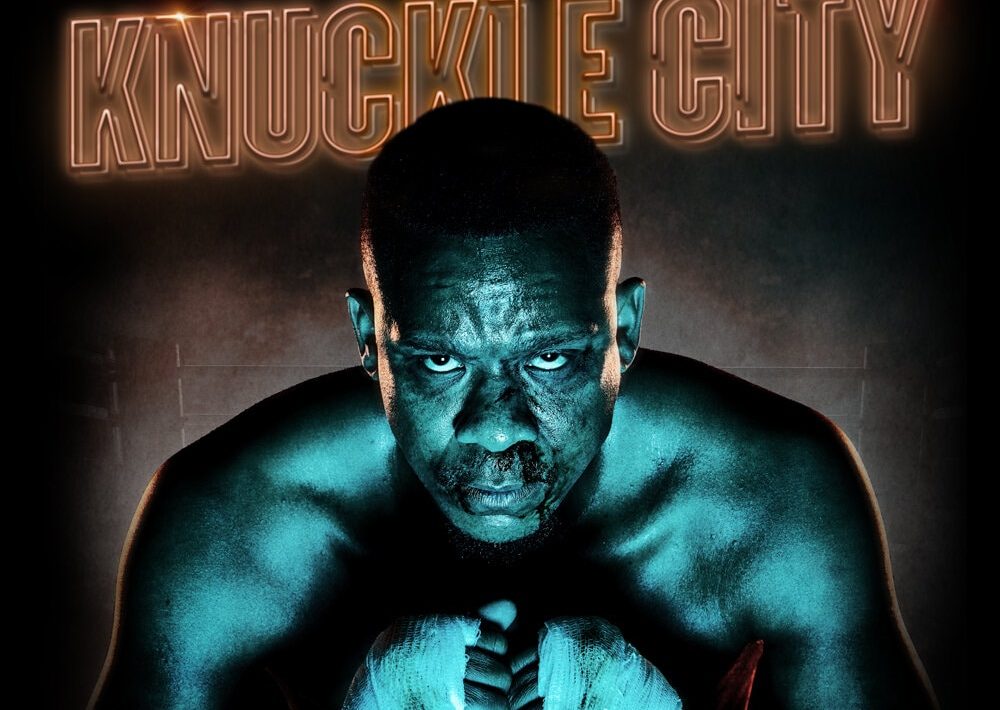

While watching Knuckle City by Jahmil X.T. Qubeka I started thinking about the South African blaxploitation cinema. And no one need to be convinced that the film by a recognizable artist from South Africa is a blaxploitation cinema. Knuckle City tells the story of an aged – though talented and being in a brilliant form – boxer, dreaming of fighting for the championship. The obstacle to success is his origin (he lives in slums) and the criminal underworld strictly controlling who fights, who wins and who loses. By entering the path to make his dreams come true, the hero is caught up in a complicated network of local power – he will have to fight on many levels, including his own past.

The film by the South African director can be seen as a lost work of blaxploitation from the 70s. There is some charm in it, but also some doubt. After all, the big problem of exploitation cinema – by the way already processed many times, e.g. by Spike Lee or Raoul Peck – was the stereotypes, perpetuating the harmful and false image of the black community. In fact, not every African American (or African) necessarily had to be a gangster, dealer or a scamp. So why is Knuckle City using this archaic subgenre (at least in this form) today, without even processing it?

The answer should be sought in the fact that, although the black communities were united by the struggle for racial equality, American and South African blaxploitation cinema had different roots. For some, American blaxploitation was a tool for empowering Black people, for others it was a harmful way of perpetuating fossilized racial and ethnic images. There is also no doubt that the genre – due to its growing popularity not only among African Americans – has been absorbed by Hollywood[1], and its elements have permanently enrolled in mass culture.

Meanwhile, blaxploitation cinema in South Africa was implemented by the Whites[2] and was intended to keep the masses in check by means of entertainment (a huge difference, if you think about it). But unexpectedly, as part of this apartheid control machine, productions with subtle subversive elements began to appear – and some of them even undertook a complicated fight against censorship. Such an example was Joe Bullet from 1973 (eventually removed from cinemas by censorship, which decided that it was a dangerous film – despite its correctness and lack of criticism of the system – because it supposedly could prove that the Blacks have some driving force).

Even if blaxploitation in South Africa was a cinema largely produced by the Whites and was intended to consolidate the violent system, it gave the Blacks a substitute (even if false) of their own culture and a context through which it was easier to build an identity. With the collapse of the regime, the blaxploitation cinema was almost completely erased – so that the renewed versions of many films (Joe Bullet was finally digitally renovated in 2014) would not return until years later, in the new millennium[3].

In this context, Knuckle City is a film-postcard given to the genre. Unfortunately, it is nothing more than a postcard. Sure, the film defends itself with the fact that there are practically no Whites in it, that it focuses actually only on the black community. But this is a tediously homogeneous community – made up of slum dwellers, speculators living of boxing betting, and gangsters.

Although pure entertainment is a tradition for South African cinema of exploitation, the genre is asking for intellectual overwork. Knuckle City is an attractive film at the basic entertainment level, but it also requires knowledge of the historical context – otherwise it may be offensive to some. Except that this context requires a comment – for a person outside South Africa, the film will not be clear – which is missing in the film by Jahmil X.T. Qubeka.

One can get the impression that the South African artist’s film will sell

better locally – this is not a

production that will appeal to a wider audience. Nevertheless, it is a good

excuse to familiarize oneself with the extremely interesting history of South

African cinema.

[1] Well, that’s how neoliberalism works. It absorbs and strives to universalize the Other, including him in a system in which the only equality is that everyone is equally exploited. Ethnic minorities – just like the poor – are given the false hope that in the future they will be able to improve their condition.

[2] It was even subsidized. Cinema in South Africa has been divided – like most things in apartheid – into “A-scheme” (White cinema, large subsidies) and “B-scheme” (Black cinema, small subsidies).

[3] You can read more about South African blaxploitation HERE.